Books: The Good, The Bad and The Classically Boring

A good book is not hard to find. But, once you have landed a bad one, it’s difficult to know what to do. My husband has been reading a groaner. By all accounts, it is supposed to be a great read. It’s a classic, one found on most recommended reading lists, one that I have not read but fully intended to, until he shared his deep discontent.

“This is supposed to be a great book, right?” he asked.

“Yep,” I replied. “It’s a classic. It’s got to be good.”

He periodically revisited the paperback over the last couple of weeks. He’d settle into his chair with a familiar grimace on his face.

“Still trying to finish, huh?” I asked.

“Trying,” he replied.

“Not exactly a page turner, is it?”

“I thought for sure it would get better by now,” he said, yawning.

“Maybe it would help if you stayed awake while reading,” I offered.

But he didn’t hear me. He was too busy forcing his eyes across the page.

Back in school, I always thought that the reason assigned reading was so distasteful was because we were made to do it. In the library, I could always find something that I would willingly read, unless, of course, it was for a grade. Assigned reading to me always felt a little like assigned eating. Some books are Brussels sprouts. Some books are a seven-course meal, a treat for all the senses. But now I know that assigned or not, some books are simply full of that regrettable Brussels sprouts aftertaste.

One of the books that most students read that I somehow escaped was “To Kill a Mockingbird.” Any decent Southern writer would be ashamed to admit that publicly, so I decided that at age 41, it was high time I read this contemporary classic. It was without a doubt the best book I have ever read. Harper Lee’s timeless story tells the captivating tale of young Scout and her brother Jem and father Atticus Finch taking on a lonely battle with racism and injustice in the small Southern town of Maycomb, AL during the Great Depression. If books were edible, this one would be the finest lemon meringue pie to be found on a café counter. In my book, it’s a must-read.

Since those years in high school English and college courses in composition, I realized teachers did me a large favor when they insisted I read Dante and Milton, Shakespeare and Poe. If nothing else, their intricate plots and complex theories and iambic pentameter of poetry showed me that the beauty of books is within the eye of the beholder but the character is in their content.

Some things we read because we must. Some things we read because we will. And some things we read because we should if we want to expand our horizons and learn from our history as humans.

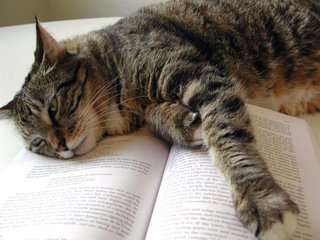

Now and then, I try to read an author whom my English teachers might have recommended, like William Faulkner. I have a copy of “Light in August” shoved in my nightstand. I have read the same 45 pages a half-dozen times. I am told by Faulkner enthusiasts to just keep trying, that one day, the mile-long sentences and minute descriptions will fall away into a dreamy endeavor into fine Southern literature. My latest attempt ended in a deep catnap, which I am certain is a reflection of my inability to remain conscious on a lazy Sunday afternoon and not of the author’s ability to keep me entertained ― which brings me back to my husband’s latest wrestling match with great literature.

“Is it any better?” I asked.

“No, not really,” he sighed. “But, I’m almost finished!” About fifty trembling pages rested in his right hand, just below his sagging eyelids.

At http://www.classicreader.com/, readers can access 3069 works of literature by 320 different authors. Classics, because they have stood the test of time, warrant our attempt to read them. They connect us to invaluable stories of all the things we still struggle with today, like how to finish a bad book when it is all too easy to drift off to sleep and wrestle with dreams of Brussels sprouts.

Send an email to

Send an email to